Roberto Fernández Retamar, an internationally respected scholar and poet from Havana, Cuba, passed away in July of this year. He was an essayist, literary critic and President of the cultural organization Casa de las Américas. In his role as President, Fernández also served on the Council of State of Cuba. An early close confidant of Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, he was a central figure in Cuba from the 1959 Revolution until his death. He served as a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Havana, wrote the critically acclaimed Caliban: and Other Essays and founded the Casa de las Americas cultural magazine.

I had the honor of interviewing and corresponding with Fernández several years ago while researching my doctoral dissertation. He was a true art lover and remarkable intellect. He is known for, among other things, creating the term Post-Occidental (which is a reference to cultures in the Americas that were once permeated by western ideologies, only to move beyond the ideologies/mentalities/systems embraced by the west or the Occident). Along with scholar Edward Said, he pushed the international dialogue concerning Post-Colonial Studies to the forefront of global trans-cultural understanding and communication. Fernández loved the art of Robert Rauschenberg (an American born in Texas). This is special because Rauschenberg was a wealthy, white, American product of capitalism. It can be argued that western capitalism has been a powerful destructive force in Cuba since it earned its independence in 1898. Yet, Fernández fully understood that in a globalized world the exchange of culture and knowledge was not just inevitable, but necessary and beneficial.

Rauschenberg had an exhibition opening in Havana in 1988 and it was not well received, for many reasons I shall not get into here. Yet, Fernández wrote of Rauschenberg, “It is understandable that a man with such a passion for incorporating new things should travel around the world setting up camp in the most remote places, enriching them with new visions, born of those places. Of course, no one should look for the spirit of those peoples in such visions, but rather these should be sought in the spirit of Rauschenberg himself. A spiritual man descended out of Whitman and Hemmingway, his works, like huge collages, take what they need from the world.”

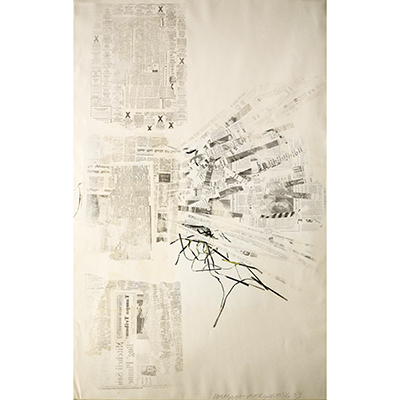

The Mulvane Art Museum owns a work called “Coconuts” by Rauschenberg (shown left) that is currently on exhibit in the 2nd floor north gallery. It is not on the surface a uniquely American work of art. It does not display red white and blue, an American flag, apple pie, or the Statue of Liberty. However, just under the surface is a remarkably American comment about art, pop culture and everyday American life. This is a part of how Rauschenberg communicated. He sought the subconscious cultural elements that those of any particular culture share. He used them in an attempt to have us embrace our differences and recognize our similarities. According to Fernández, he did it in a way that was reminiscent of profound poetry.

Although Rauschenberg’s art is appreciated on a global scale, it is derivative of Western mentalities. It fits into a dialogue of Western critical theory concerning Post-Modern art. He uses the flotsam and jetsam of Western culture in unusual contexts to instigate reactions in viewers. In “Coconuts” he uses the printed word as an aesthetic tool to foster a notion of familiarity (for those that see newsprint regularly).

The issue artists and museums face in an increasingly globalized art world, and an idea with which Fernández and Rauschenberg engaged, is how to successfully communicate and share among peoples and institutions whose contexts are so different that misunderstanding or offense is likely. In order to have meaningful communication in a post-colonial globalized world we must recognize the constructs within which we operate and how they are different from those of others. At the core of the issue is culture, identity and agency. The museum must adapt to a post-colonial and globalizing world where national and cultural identities are not always easily definable, yet they certainly color how we view the world around us. Being Cuban and a man that loved his country, Fernández embraced these communications in the arts and in global contemporary intellectual dialogue. It is a position the Mulvane must maintain as well.

Fernández’s comments about Rauschenberg encapsulate some of the most difficult challenges faced by American and European museums today. We cannot present cultural material as if it is “the spirit of a people.” We curate exhibits with the knowledge that our voices are skewed by our personal, cultural, social, temporal and global contexts: a notion that Rauschenberg used in his art. This is also true of museum professionals in Post-Occidental cultures like Cuba that have recently begun to have a sense of agency in a global context. The complex issues that manifest from these phenomena are increasingly prevalent as the world is further globalized. Yet, present the information we must. Even if this includes acknowledging the powerful and lingering miasma created by acts such as slavery, colonization, genocide and religious zealotry. Time does not easily heal these wounds. And maybe it shouldn’t. This is the continually new globalized world. We must come to understand our inheritance of new realities (and old ones). Museums have an opportunity to be leaders in this endeavor. Museum professionals have a responsibility to do so. Navigating this issue is a part of what it is to be a 21st century art museum.

Rest in peace Roberto. Your legacy touches many. I would like to think, sometime, we might once again talk of art.

Brett Beatty, PhD.

Assistant Director, Operations and Programs

Mulvane Art Museum