Between the Lines

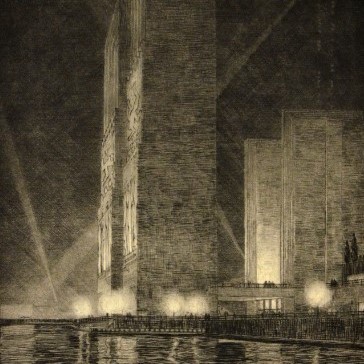

Gerald K. Geerlings, Electrical Building at Night, 1933, etching

As an architect and printmaker at a time of rapid urbanization, Gerald K. Geerlings became known for his cityscape etchings from 1920-1940. Depicting the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, where commercial sponsorship and technological innovation were the main themes, this work captures the entrance to the electrical exhibit. The buildings’ carved figures represent Light and Sound. Lack of color makes the contrast between dark and light central to the piece, emphasizing the importance of electricity at the height of the Great Depression, when people turned to technology for a better future. Looking up from below, the perspective captures the sense of grandeur and awe observers at the fair felt. This is an early example of the US defining itself as a capitalist nation on a global stage. Like this artwork, the fair advertised an idealized picture of American life.

Text by Elly Keyes

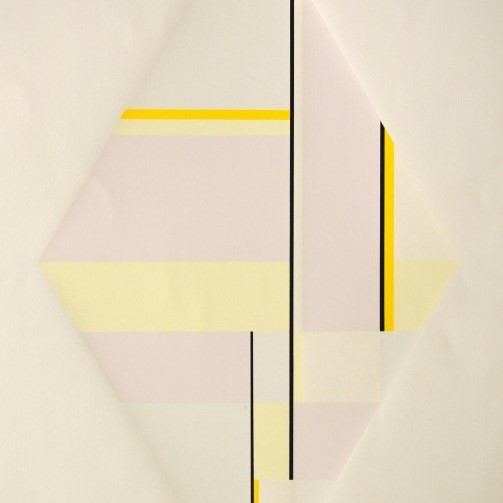

Ilya Bolotowsky, Untitled IV, n.d., serigraph, 29 1/2 x 22 in.

Ilya Bolotowsky (1907-1981), a Russian-born American abstract artist, significantly contributed to the Concrete Art movement, characterized by precise geometric forms and a commitment to visual clarity. Bolotowsky was influenced by Neoplasticism, a style led by Dutch painter Piet Mondrian. Mondrian’s pursuit of an enlightened society of idealized harmony through geometric abstraction, primary colors, and grid structures inspired Bolotowsky's artistic principles. Latin American modern art and early Russian Constructivism share parallels with these principles, embracing universality through geometric forms and a "truth to materials." As a Russian expatriate in the United States, Bolotowsky similarly embraced these principles, introducing softer forms, a more varied color palette, and a wider variety of canvas shapes within the context of American abstraction. The stylistic affinity shared with these communist movements raises questions about his political leanings. Could this be read in defiance of the Soviet Union? Or is he making a more nuanced statement about universality across ideological lines?

Text by Jett Terrill

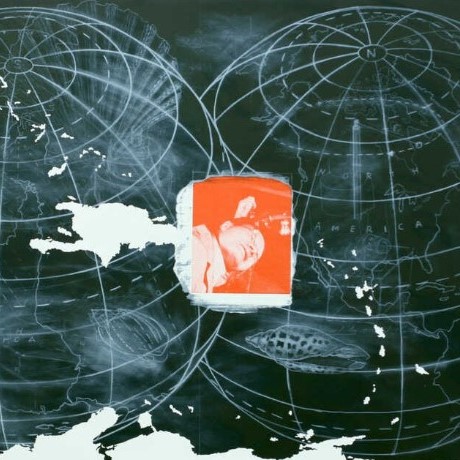

Vernon Fisher, Perdido en el Mar, 1989, color lithograph, 30 x 37 in.

Perdido en el Mar features a global map divided into two spheres, one of which contains an upside-down South America, the other of which contains a right-side-up North America. The title, translated from Spanish to mean “Lost at Sea”, suggests a sense of disorientation and uncertainty that pervaded the world during the Cold War. The figure at the center of the composition could reflect the disorienting personal and collective experiences of those living during this period. The white marks are reminiscent of islands located in Latin America and hint at the cultural and political exchanges between North and South America, given that many Latin American countries served as a battleground on which the two superpowers of the Cold War vied for power through backing opposing regimes. The fact that one of the globes is upside down may hint at their attempt to use this region in an effort to tilt the balance of power.

Text by Zach Stephens

Joseph Konopka, 4th of July, 1974, acrylic on canvas, 40 x 44 1/4 in.

The female figure in Joseph Konopka’s painting 4th of July looks carefully down at a tray of white frosted cupcakes topped with decorative American flags. Set in what appears to be a backyard barbeque, the scene initially resembles a carefree celebration of a national holiday. In 1974, the year the painting was made, however, many Americans did not feel very patriotic. Protests raged throughout the country against America’s involvement in the Vietnam War, one of many proxy wars that defined the Cold War, which had claimed the lives of tens of thousands of American soldiers. The abstraction of highlights and shadows into simplified blocks of color recalls the early 20th-century style of Precisionism, which was used to depict the excitement of early American urbanization. The muted colors, however, are reminiscent of an old photo that has faded over time. In this light, perhaps Konopka’s painting represents a nostalgia for the idealism of the past, when patriotism came more easily.

Text by Kana Furuichi and Madeline Eschenburg

A Choice to Make

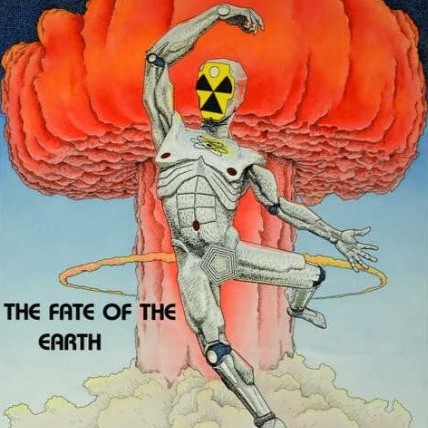

Michael Jacobson, Fate of the Earth, 1985, lithograph, 28 x 18 in.

Duck and cover! Get your umbrellas out! A nuclear bomb just went off! The lithograph pictured here was created by Michael Jacobson in 1985 while attending Washburn University. It depicts a large silver cyborg standing over a small gold cyborg holding an umbrella. The quote below the image is by Jonathan Schell, from his book The Fate of the Earth, which is an abstract discussion of survivability and balance of power during nuclear proliferation and consequences humanity would face. The earth under the silver cyborg (representing nuclear destruction) is being swept away, while an atom bomb explodes in the background. In the style of a political cartoon, this artwork illustrates Schell’s warning that if we continue to allow nuclear proliferation, not only mankind, but also the earth, may face annihilation. Both Schell’s book and this artwork challenge humanity to choose disarmament before it is too late.

Text by Hailey Houser

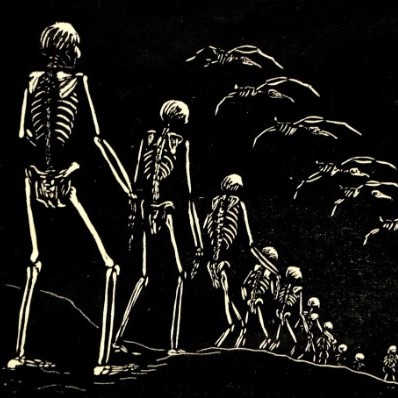

Alberto Garcia Maldonado, Hacia el Mismo Punto, n.d., woodcut, 6 x 8 in.

When considering Mexican art during the 20th century, collectives such as the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP), who used woodcut prints to advance social causes, are well-known, but new voices have recently been rediscovered. One such artist, Alberto Garcia Maldonado, puts forth a perspective that could have socialist leanings, painting “calaveras” or skeletal caricatures all the same, perhaps suggesting a collectivity. In similar fashion to the TGP, he depicts calaveras using the expressive and accessible medium of woodcut prints to convey an idea of desolation, using a prominent black ink background alongside a defoliated landscape. The number of calaveras depicted match the number of Latin American countries during that time. With Mexico and many Latin American countries experiencing political unrest during the Cold War period, we can see a potential commentary that despite our differences, in death, we all converge at the same point.

Text by Alexis Muñoz

Alberto Garcia Maldonado, Coox Coox..., 1951, woodcut, 8 1/2 x 11 1/2 in.

Alberto Garcia Maldonado is a relatively unknown Mexican woodcut printmaker from the 1950s who drew inspiration from Mexican and Mayan cultural beliefs regarding death. In Mayan belief, death was not feared but respected, as seen in the popularity of skeletons, or “calaveras,” in Mexican art up to the present day. From the position of the kneeling figure, we can surmise that he is pleading for and protecting the lives of his family, even as Death beckons them all to follow. Expressive lines and dramatic contrast made woodcut prints a powerful medium to address social and political power dynamics. The Mexican Revolution was, in part, a social revolution which sought to redistribute wealth to the peasantry, a goal shared with communism. Maldonado’s focus on the desperation of what appears to be a family of limited means suggests that such goals were not fully met in the Yucatán Peninsula, the artist’s home.

Text by Cori Singleton

David Hockney, Corpses on Fire, c. 1969, etching, 9 3/4 x 10 1/4 in.

This work illustrates a scene from the Brothers Grimm fairy tale about a boy who wandered the world to learn the one thing he could not understand: fear. He spent the night beneath seven men who had been lynched. He lit a fire and lowered their bodies to warm them, igniting their clothing. The two human figures in this work appear to suffer, as seen by the burnt lacerations across their bodies. However, their faces remain pale and expressionless, revealing that they are already dead. Although Hockney is well known for his brightly-colored Pop paintings, this artwork from his etching series Six Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm presents darker themes inherent in the Gothic stories. While not directly related to politics of the time, the inclusion of fire and darkness in this etching could reflect the Cold War fear that the spread of Communism would “set the world on fire.”

Text by Lee Turner

Karl A. Menninger, Image of Nuclear War, 1972, acrylic

This abstracted, expressive painting depicts a nuclear explosion in highly contrasting colors so bright they almost seem to battle each other for space on the canvas. Karl A. Menninger, a world-renowned psychiatrist and hobbyist painter during the later years of his life, commonly included this “warfare of colors” within his art. The subject matter of the painting is likely related to Menninger’s involvement in the anti-nuclear movement during the 1970s and 1980s. The small scale of the trees at the bottom of the canvas, contrasted with the vastness of the red and golden sky above, embodies the sense of fear and danger that instigated the anti-nuclear movement during the Cold War.

Text by Anna-Marie McIntyre

What Now?

Peter Turnley, Romanian Revolution, Bucharest, Romania, 1989, archival pigment print, 20 x 24 in.

Nicolae Ceauşescu, the communist party dictator of Romania, implemented policies that caused the suffering of Romanian people for years, leading to the Romanian Revolution in December 1989. These riots resulted in the death of over 1,000 civilians, the execution of Ceauşescu, and power taken by the democratic National Salvation Front. This photograph was taken the day after the execution and transition of power. It shows a young man turned away from the camera, holding the Romanian flag with the center cut out, before a crowd of civilians scattered among parked military vehicles. As an act of revolution, protesters removed the communist symbol from the flag to represent their desire for change. Turnley’s framing hints at a sense of uncertainty over the future of Romania after communism. This revolution was one of many which led to the collapse of communism in the Eastern bloc and the end of the Cold War.

Text by Kelli Cummings

Peter Turnley, Coal Miners, Knovokuznetsk, Siberia, Russia, 1991, archival pigment print, 20 x 24 in.

Explore the human side of the Cold War through Peter Turnley's lens. This photograph reveals the resilience of Soviet women miners during the end of the Cold War. Amidst coal miners’ strikes and political shifts of late '90s Russia, Turnley blurs reality and staging, prompting us to question photography’s purpose, in a county where Socialist Realism was the only accepted art form for so long. A single source of light illuminates an understated scene of laborers on break. Who are these unnamed workers? Do they smile for the camera naturally or pose intentionally? How does the image shed light on overlooked individuals and challenge the Cold War’s narratives? Miners in Novokuznetsk offers a unique perspective on the Cold War, emphasizing visual stories rather than names and inviting us to reconsider who really shapes our understanding of history.

Text by Lily Greene

Peter Turnley, Pope John Paul II with Fidel Castro, Havana, Cuba, 1998, archival pigment print, 20 x 24 in.

The Cold War ended in 1991 when the USSR collapsed. This photograph, taken seven years later, shows Fidel Castro and Pope John Paul II on a stage talking about how Cuba should be run for the sake of the country's people. Castro is pictured wearing a suit instead of his usual military clothes, a sign of respect for the Pope. The leaders mostly disagreed, as is perhaps evident in Castro’s finger being held up at the Pope, but were able to devise a compromise so the country could get the help it needed. Castro allowed the meeting to happen because he wanted to gain financial support and medical aid that had previously been provided by the USSR. The candid nature of the moment captured by Turnley could provide a more authentic view of the meeting than those showing the duo smiling and shaking hands.

Text by Amanda Conner

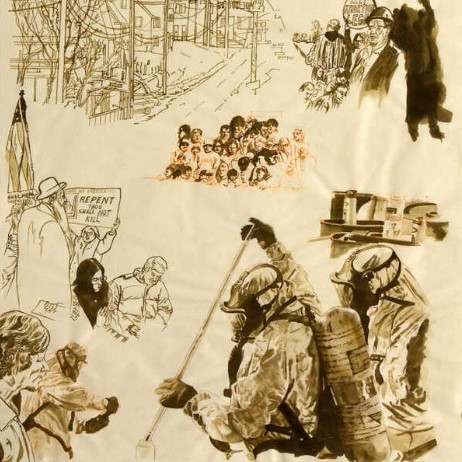

William L. Haney, Study for Toxic Eucharist, 1990, ink wash, 19 x 24 in.

In the wake of the Cold War, the world was shrouded in fear and uncertainty. The government promised a brilliant future of nuclear power, the church promised peace and love for all. But in Study for Toxic Eucharist, Haney depicts multiple protests about nuclear power and abortion rights. To the left, we see a quaint townscape with a nuclear power plant in the background. Below that, we can see a religious leader spearheading an abortion protest. Eucharist, also known as communion, is the ritual consumption of consecrated bread and wine, representing the body and blood of Jesus in the Christian faith. Nuclear power was feared for the toxic byproducts that could harm the community. Both religion and nuclear power have an ambiguous essence that, when combined, kindle the fear of the unknown. Is Haney suggesting that the things that promise the best for humanity also bring forth its worst traits?

Text by Alli Lane