The Working Class

Gods, kings, and politicians were figures typically depicted in art throughout history, while lower-class citizens were rarely represented. At the turn of the 20th century in America, artists, starting with the Ashcan School, turned their attention to the working class. The Ashcan School was a group of New York painters who captured the lower class enjoying or toiling through everyday life.

New Deal era government-funded programs such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) employed millions of Americans in response to the economic hardships brought on by the Great Depression (1929-1933). Its visual arts arm, the Federal Art Project (FAP) (1935-1943), provided work relief for artists in various media--painters, sculptors, muralists, and graphic artists. In addition, the Farm Security Administration (FSA) hired photographers to capture rural, impoverished America to demonstrate farmers’ hardships. Some artists employed during this time showed the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl’s gruesome impact on Americans. Others opted to portray rural workers in a romanticized, more positive light, highlighting the strength and resilience of American laborers, farmers, factory employees, and railroad workers.

Art is often used as a powerful tool to highlight the imbalance of wealth in the world. For example, Nicola Ziroli’s painting and Martin Lewis’ etching focus on women in the 1930s, who are undoubtedly from different socioeconomic classes. Lewis depicts a lavishly dressed woman enjoying the streets of New York, seemingly unaffected by the economic crash. Alternatively, Ziroli and Russel Limbach’s works showcase people working long, straining hours for dimes a day.

Text by Amanda Pope

Russell Limbach (b. 1904 - d. 1971)

CWA Workers, 1935

lithograph

Donation of WPA Federal Art Project

CWA stands for “Civil Works Administration,” a short-term job creation agency that provided construction work for unemployed Americans during the Great Depression. Limbach depicts three sturdy men standing in the foreground, shoveling dirt along the water. In the background, smaller men in profile appear to be depositing the dirt atop two hills, perhaps building a levee. The details of their faces are not visible, putting more focus on the labor of their bodies. As we can see here, they are hunching over, emphasizing their strength while working together to improve America’s infrastructure.

Russell Limbach was a printmaker from Ohio. He worked under the Federal Arts Program (FAP), a program that provided income to artists working in various media. Russell was the head of the Graphics Division of the FAP in New York.

Text by Cecilia Nuño-Maciel

Nicola Ziroli (Italian, b. 1908 - d. 1970)

30 Cents an Hour, 1939

oil on canvas

Donation of WPA Federal Art Project

30 Cents an Hour depicts an African American woman washing and drying dishes for a meager wage during the Great Depression. The painting was made in 1939 by an Italian artist Nicola Ziroli through the Works Progress Administration. The artist’s choice of realism, including the details of the fingers holding the cloth and the look of concentration on the woman’s face, allows the viewer to connect with her on an emotional level. In addition, the shallow picture plane and the angle at which Ziroli depicts the figure make one feel as if they are sitting right next to her. This work provides a glimpse into the realities faced by African American women during the 1930s.

Text by Jackson Nicodemus

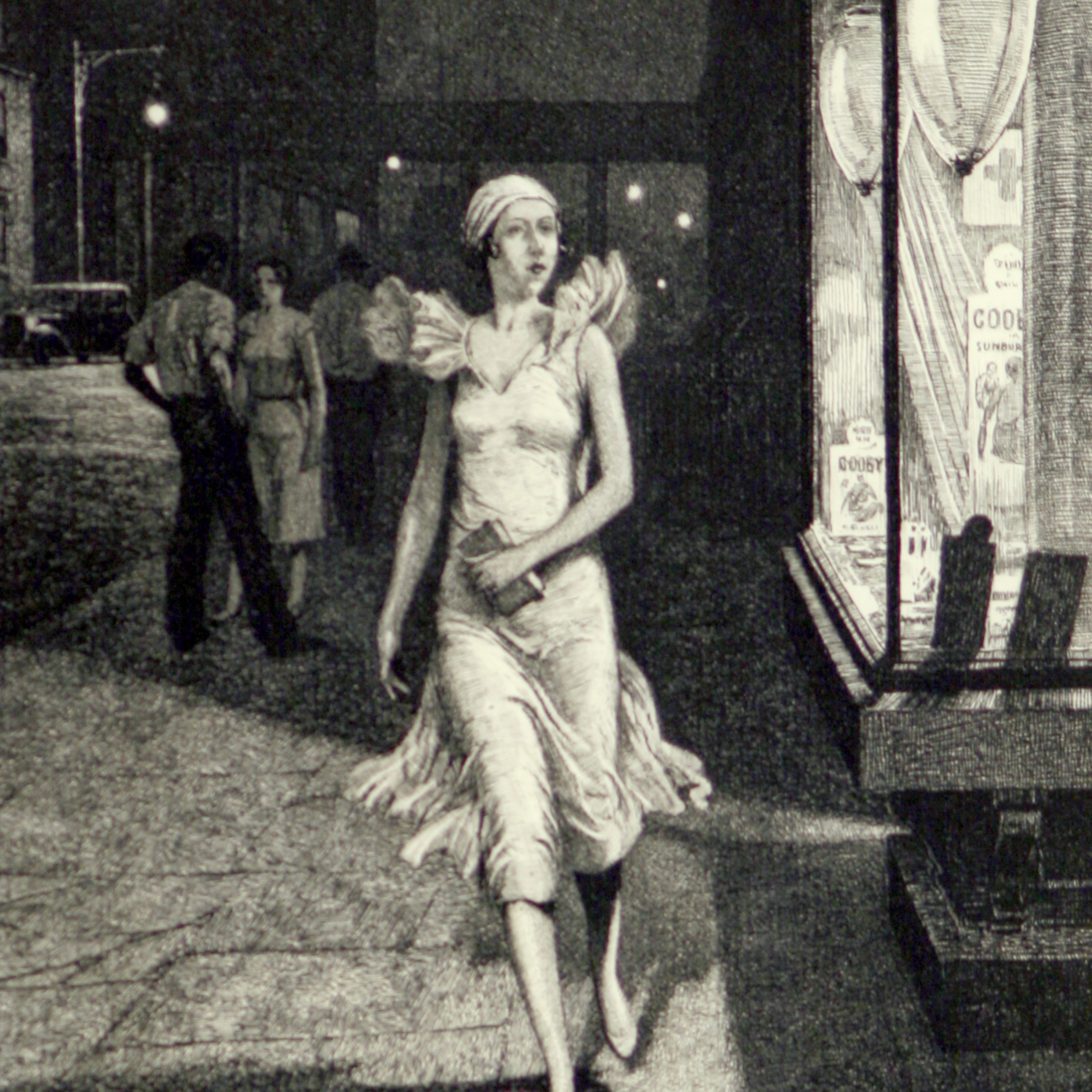

Martin Lewis (American, born in Australia, b. 1881 - d. 1962)

Night in New York, 1932

etching

Gift of Charles and Margaret Pollak

Night in New York features an unidentified woman who steals the show in her elegant dress, made ever more impressive by the light illuminating it from a store window. Her flashy clothes, the car in the background, and the consumer goods in the window differ markedly from other works in this exhibition made during the Great Depression, which focus on toiling laborers. Perhaps Lewis wanted to highlight America’s continued cultural and technological progress despite an economic disaster. Other, more plainly dressed figures also populate Lewis’s etching, seemingly going about their daily lives. Contrasting with the central figure, they appear to be more like the average New Yorker of the time and provide a fuller picture of the city’s population.

Lewis made most of his art during the 1930s and rose to prominence as a renowned etcher, eventually earning fame and recognition by the Chicago Society of Etchers.

Text by Jordan Dickens

Feminism

Historians identify the development of feminism in the United States as occurring in three waves. The first wave consisted of women fighting for the right to vote in the 19th and early 20th centuries, culminating in the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920.

The second wave occurred from the 1960s through the 1980s and focused on women’s social, sexual, and reproductive liberation. However, the movement centered on the rights of white, middle-class women. Finally, the third wave of feminism, which emerged in the mid-1990s, emphasizes a sense of inclusion, connecting feminism with the fight for racial, class, and LGBTQ+ rights.

Some have theorized that we are now entering the fourth wave of feminism-- one that calls for justice and accountability against harassment, abuse, censorship, and unequal pay and demands the bodily autonomy that women have been denied. In her book All the Rebel Women: The Rise of the Fourth Wave of Feminism, Kira Cochrane writes, “A new energy coursed through society,

thousands of feminists suddenly rising, suddenly angry, ready to strike against an image and treatment of women that no longer seemed remotely ironic or funny.”

Elizabeth Layton’s work addresses the censorship women, especially elders, often feel in our community. Janice reveals the trauma of the domestic violence that many women face. Miss America Contest explores how women are exploited for their beauty. Finally, Female Grand Dragon at Ku Klux Klan Rally reveals one extreme example of how the feminist agenda has not always aligned with other fights for social justice.

Text by Mary Smith

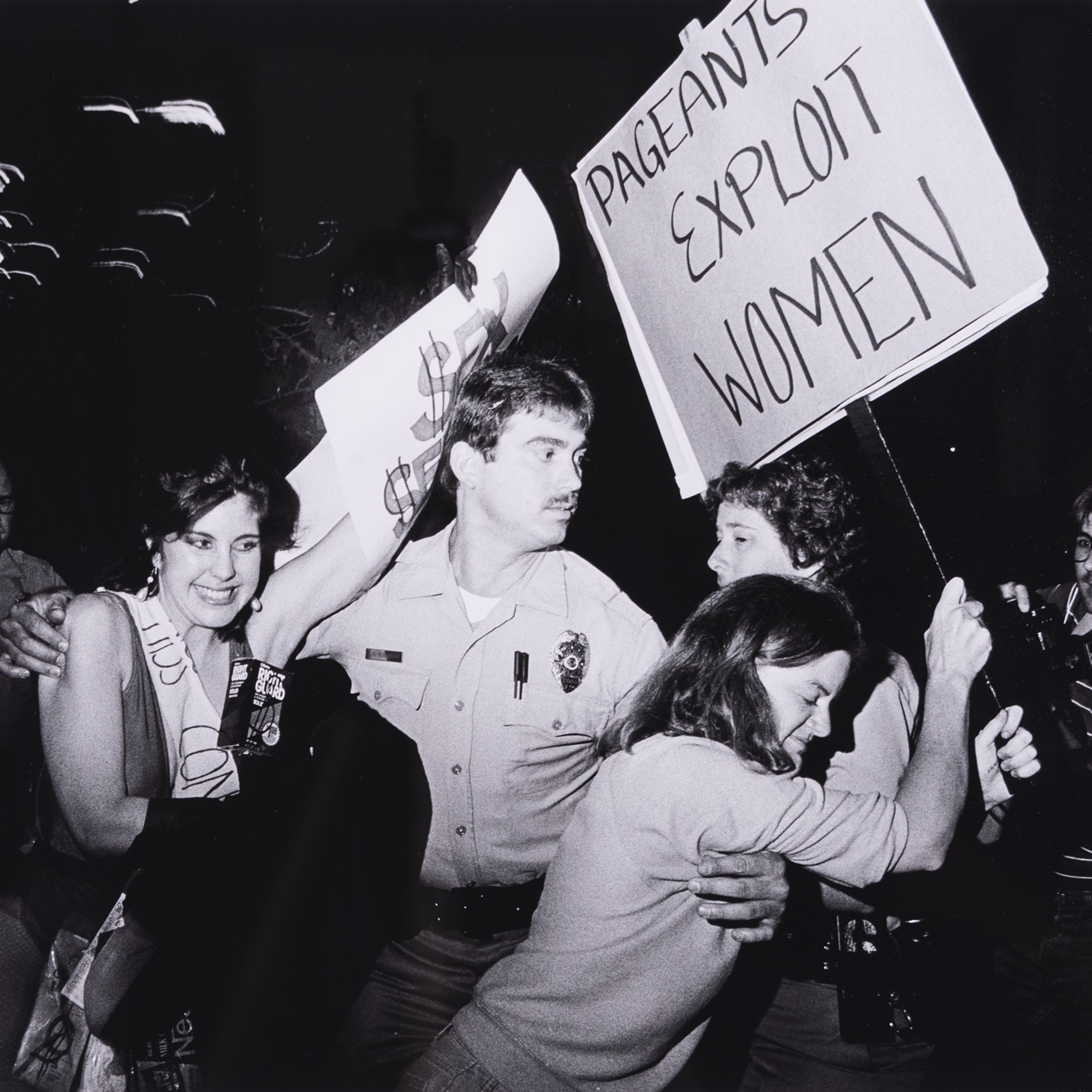

Donna Ferrato (American, b. 1949)

Miss America Contest, San Diego, 1986

pigmented inkjet print

Gift of Joseph Keough

Two female protestors are escorted away by police officers outside the 1986 San Diego Miss America Contest. One woman smiles wide while the other struggles against the officer, holding a sign that reads "PAGEANTS EXPLOIT WOMEN." This photograph is from the series Holy, published in 2020, consisting of pictures of women taken over the last 50 years across the United States. Ferrato states Holy is "about the unleashed power of women. What women have gained over the last 50 years. The hard-won freedom that women are losing."

Feminist activists have long argued that beauty pageants promote the antiquated notion that women's value lies in their beauty, purity, and agreeability. Ferrato's photojournalism captures the spontaneous moments of real life, documenting the world in unrehearsed snapshots. While the light bathing the figures seems artificial, the multi-directional chaos of this scene contrasts starkly with the tightly controlled refinement of most beauty pageants.

Text by Courtney Cox

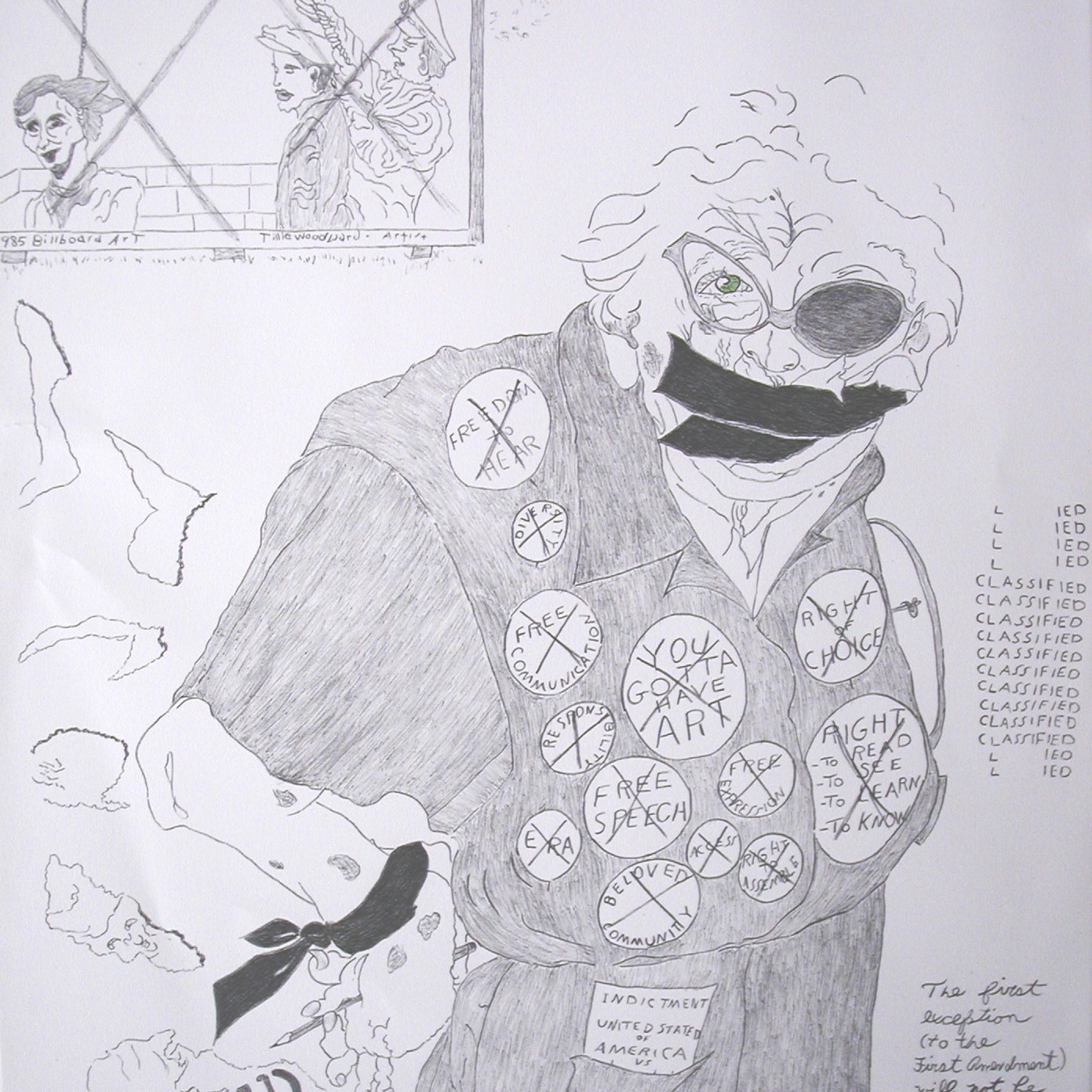

Elizabeth Layton (American, b. 1909 - d. 1993)

Censored, 1989

lithograph

Donation of Don Lambert

Elizabeth “Grandma” Layton depicts herself as a prisoner with her mouth taped shut, hands tied behind her back, and drawings torn up behind her. Items around her, such as a crossed-out billboard in the top left corner, a tumbling statue underneath it, crossed-out pins on her jumpsuit, and a quote about the first amendment in the bottom right corner, represent censorship. The jagged, expressive lines, suggest her reactions to current events, like the 1989 Tiananmen Square riots in China and the 1985 censorship of an I-70 billboard by artist Tilly Woodward that featured the hangings of Russian freedom fighters by Nazi soldiers. These details collectively represent Layton’s attitude towards ageism and sexism, the repressive nature of totalitarian regimes, and the hypocrisy of censorship in a supposedly democratic nation.

Text by Kaitlynn Ray

Donna Ferrato (American, b. 1949)

Janice “Living With The Enemy,” Boulder, CO, 1984

archival pigment print

Gift of Cory Herrick

Even though the United States has enacted some of the most protective laws for women, such as the 1994 Violence Against Women Act, domestic abuse continues. Victims of domestic abuse are exploited and abused by their partners and by a larger judicial and political system that fails to bring justice. There is a sense of defeat in Janice’s eyes, who has just witnessed her best friend being murdered by her husband.

Text by Mary Smith

Civil Rights

The American Civil Rights Movement was a mid-twentieth-century fight to end racial inequality and legalized discrimination. During the Reconstruction Period (1865 - 1877), the government ratified amendments intended to secure equal rights for African Americans. However, many states resisted these changes, implementing Jim Crow laws that enforced segregation in the South. Participants in the Civil Rights Movement used mass protest to draw attention to systemic

inequality.

Gordon Park’s photograph Sunday Morning depicts a couple who migrated north after living through segregation in the south. Lonnie Powell’s painting ... Go Home viscerally recounts the hatred faced by black children as they integrated previously all-white schools, following the 1954 supreme court ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education.

In 1957 President Eisenhower signed the Civil Rights Act, allowing for federal prosecution of anyone who suppresses another’s right to vote. Despite this, African Americans continued to face obstruction of this right. Edward Navone’s painting In Memoriam depicts the remains of three volunteers working in Mississippi on voter registration who members of the KKK murdered. Jacob

Lawrence’s print Confrontation at the Bridge illustrates a march organized in response to voter suppression in Alabama which ended in bloodshed when state troopers and locals violently attacked the protesters. Roger Shimomura’s Yellow No Same reminds us of the horrors faced by Asians and Asian Americans after the attack on Pearl Harbor during WWII. Finally, William Haney’s drawing speaks to the imperialist origins of our nation, built on land stolen from Native Americans.

The American Civil Rights Movement is historicized as ending in the late 1960s; however, photographs like Peter Turnley’s Rodney King Riots reveal that the fight for racial equality continues today.

Jacob Lawrence (American, b. 1917 – d. 2000)

Confrontation at the Bridge, 1975

serigraph

Museum purchase

The figures in this print are composed of simple, flat blocks of bold colors. However, the artist has imbued them with vivid expressions, depicting their anger, fear, trepidation, and resilience.

Confrontation at the Bridge illustrates the first attempt of three marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to protest local interference with Black voting rights. On March 7, 1965, the marchers were stopped on the Edwin Pettis Bridge by a group of State Troopers who forced them to retreat using whips, nightsticks, and tear gas, represented here by the snarling dog to the left. On March 25, the protesters successfully completed the march, thanks to federal protection offered by President Lyndon B. Johnson. Brave acts of protest like this inspired the passing of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

Edward Navone (American, b. 1937)

In Memoriam: Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, James Earl Chaney, 1964

oil on canvas

Donation of Washburn University Class of 1965

In the summer of 1964, three young men were abducted and murdered for volunteering in Freedom Summer, a campaign to register Black voters in Mississippi. Rather than intimidating activists, the crime had the opposite effect. In the two years after the murders, one hundred thousand African Americans had registered to vote.

Inspired by the events, Navone created this painting of three skeletal remains. When asked about the painting, Navone said that he “really wanted to show people that although they had passed away, they were still in a sense alive and carrying on.” To achieve this, he painted the middle figure looking up to suggest a brighter future.

Text by Brittany Crocker and Aaron Woodbridge

Roger Shimomura (American, b. 1939)

Yellow No Same #1, 1992

lithograph

Museum purchase

Yellow No Same is a series of twelve lithographs that explore conflicting identities. The lithographs depict actors from traditional Japanese woodblock prints and Japanese Americans separated by barbed wire.

Shimomura and his family were imprisoned in an internment camp along with approximately 127,000 other Americans in the United States following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. The U.S. Government designated second or third-generation Japanese American citizens as people having “Japanese ancestry,” regardless of their respective American identities.

Text by Jace Reeves